NASA’s hopes for a Monday launch of the massive Space Launch System rocket from the Kennedy Space Center on a test flight to the moon are on hold for at least a few days after engineers were unable to resolve an engine problem.

One of the four SLS core-stage engines failed to reach the proper temperature for launch, prompting the Artemis I mission’s launch director to scrub the planned Monday morning liftoff.

With just 40 minutes left on the countdown, scheduled as early as 8:33 a.m. ET, flight controllers had called a hold while engineers evaluated the problem.

Engineers were dealing with a series of issues in the runup to the planned launch. First, lightning strikes at the pad on Saturday initially caused some concern, but officials later said there was no damage to the vehicle, the capsule or ground equipment. Then came a 45-minutes weather delay early Monday morning that slowed the procedure for filling the core stage with its hydrogen fuel. A leak was also discovered, but resolved.

“We don’t launch until it’s right,” NASA administrator Bill Nelson said after Monday’s decision to scrub.

Putting the flight on hold was “illustrative that this is a very complicated machine, a very complicated system, and all those things have to work,” he said.

“You don’t want to light the candle until it’s ready to go,” Nelson, himself an a former space shuttle astronaut, said.

The next launch opportunity for the uncrewed Artemis I launch is Friday. The flight is meant as an initial step in eventually returning humans to the surface of the moon — a flight that could take place as early as 2025.

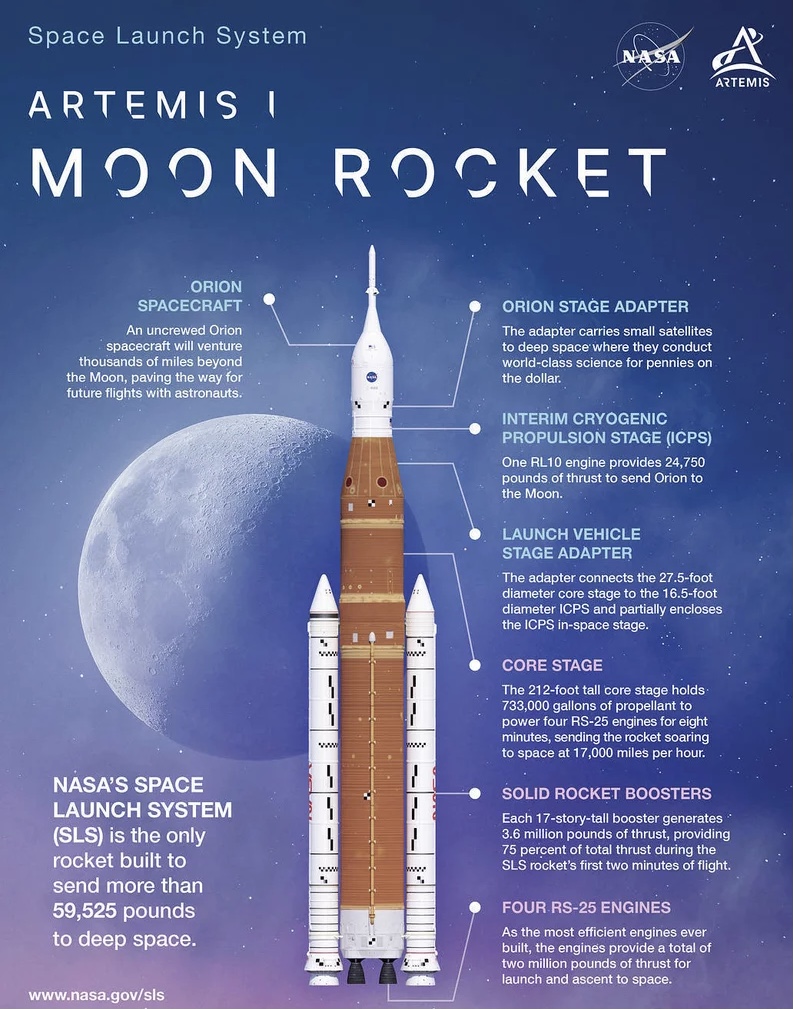

The 30-story-tall SLS rocket, topped by an uncrewed Orion spacecraft, was rolled out earlier this month to the same historic launch complex used by the mighty Saturn V during the Apollo moonshots that ended in 1972

This first mission of Artemis — named after the twin sister of Apollo — is a trial run of hardware needed to go back to the moon for longer stays and more science.

“It is an incredible step for all of humankind,” NASA astronaut Nicole Mann told NPR’s All Things Considered. “This time going to the moon to stay. And it’s really the building blocks for our exploration to Mars.”

The Artemis program, expected to have an ultimate price tag of $93 billion, promises to refocus NASA’s long-term human space-flight goals, paving the way for eventually establishing a crewed base near the moon’s south pole and crewed missions to Mars.

But one key piece of the program — the vehicle that will actually land on the moon’s surface — will not be part of the first Artemis mission. Elon Musk’s SpaceX has been contracted to build a lunar variant of its Starship to take astronauts to the surface. The vehicle has yet to be tested in orbit. Another component of the original Artemis program, Gateway, a sort of deep-space way station for astronauts to and from a future moon base, is also still under development.

It’s a modern mission with a retro look

The SLS sports stretched versions of the solid-rocket boosters used by the space shuttle, which last flew more than a decade ago, as well as four RS-25 engines that were refurbished and are being reused after previously flying on shuttle missions. The rocket’s upper stage will be powered by a type of engine first developed in the late 1950s.

Boeing is the prime contractor for the SLS core stage and upper stage. Boeing’s chief engineer for the SLS program, Noelle Zietsman, says that in building the giant rocket, engineers drew from the “foundations and fundamentals” of the Saturn V and space shuttle years.

“We’ve got our missions that we’re focused on right now to the moon,” she says. “But [the SLS] is for deep space exploration. … So, the capability is much greater and larger beyond just the moon landing.”

The cone-shaped Orion spacecraft, which will take up to four astronauts into lunar orbit on future missions, resembles the Apollo-era “command module.” Finally, a European service module, attached to Orion, is comparable in function to Apollo’s service module and will provide propulsion, electricity, water, oxygen and climate control to future crews.

The six-week Artemis I test flight will send Orion into what is known as a distant retrograde orbit, an oblong circuit that will take it just 62 miles from the moon’s surface at one point and well beyond the moon at another.

Reported by National Public Radio/USA