A day after the official end of this year’s United Nations COP29 gathering of countries committed to halting climate change, negotiators struck a last-minute deal for wealthy countries to help poorer countries like Liberia deal with global warming.

The so-called “finance COP” held this year in Baku, Azerbajain, had been focused on raising money to help developing nations cut their climate pollution and deal with the growing crises they face from extreme weather. African nations have contributed just 7 percent of the pollution heating the planet but suffer more of the harms of extreme weather.

Poor countries had pushed for a figure of $1.3 trillion a year, saying that was the minimum that was needed to fund their adaptation. But the final agreement set a goal of $300 billion. Though it was an increase from the last agreed figure of $100 billion, some representatives of developing countries were furious.

“It’s a paltry sum,” said Chandni Raina, a member of India’s delegation, during the conference’s closing meeting. “It is not something that will enable conducive climate action that is necessary for the survival of our country and for the growth of our people, their livelihoods.”

Mohamed Adow, director of the Kenyan think tank Power Shift Africa, said at a press conference on Friday that this was “the worst COP in recent memory.”

Taking aim at wealthy countries that built their economies over centuries using fossil fuels, Adow added, “You can’t have a negotiation if only one side is actually engaging in good faith and putting forward proposals that [respond] to the needs on the ground.”

Overshadowing the talks was the rightward political move of Western countries especially the United States. It’s expected Donald Trump will once again pull the US out of the Paris Agreement framework, under which countries have committed to cutting emissions, when he takes office in January.

This year’s COP came as Liberia is finalizing its third revised National Determined Contribution, a requirement of signatories to the Paris Agreement to detail the nation’s commitments to climate action. Vice President Jeremiah Koung told world leaders at the summit that support from the so-called Loss and Damages Fund, designed to help poor countries adapt to climate change, was essential.

He committed the new government of President Joseph Boakai to increasing its commitments to biodiversity protection, conservation of mangroves and freshwater ecosystem services.

Liberian activists were among those at the conference advocating for more funding.

“We are committed to advocating for those tangible commitments to climate finance, a Loss and Damage fund, technology transfers and increased support for adaptation and mitigation,” Beyan E. Harris, executive director of the Center for Youth Civic Leadership and Environmental Studies, told FrontPage Africa/New Narratives from Baku.

But while activists demanded more funding from the biggest emitters, critics pointed out that Liberia has some work to do to secure funding that is already available. Some funding that would be available has not been forthcoming because the country has not supplied required data, funds met other requirements to unlock funds.

One example is the $US25.6 million Metropolitan Climate Resilience Project launched in 2021 to bring relief to coast dwellers whose communities are being swallowed by rising sea levels. The massive six-year project was designed to bring a range of improvements including community-led projects to conserve Monrovia’s mangrove ecosystems, small-scale manufacturing facilities to promote energy-efficient livelihoods, and the construction of coastal defense structures to hold back the sea.

The Green Climate Fund, an international donor fund designed to help low-income countries adapt to climate change, was to fund the bulk of the costs – $ US17.2 million. The United Nations Development Fund was to pay $US1.6m, while the Liberian government was to pay $6.8m. But by January this year – three years into the project – the government had paid just a small fraction of the money. The project had slowed causing frustration among those who had expected to see benefits years earlier.

Jonathan Stewart, executive director of Agro Tech Liberia, a local not-for-profit working with Liberian farmers, is one of many advocates who would like to see more transparency in government’s strategy for dealing with climate change and funding applications.

He said after returning from COP29, the government should better include climate change action in the country’s national development agenda by allocating funding in the national budget.

“As a nation, we have taken some initial steps but we need to move forward with practical actions by strategically investing in sustainable development initiatives and holding ourselves accountable to sustainability,” Mr. Stewart said. “We must put in place an accountability and transparency framework that will inspire donors’ trust and confidence.”

There was one win for Liberia on a different front. On the opening day of COP29, Article 6 of the Paris Agreement was adopted. It paves the way for a UN-backed global carbon market. This market will facilitate the trading of carbon credits, theoretically incentivizing countries to reduce emissions and invest in climate-friendly projects.

Liberia has long been a vocal advocate of carbon trading, aiming to leverage its 6.6 million hectares of forest. It has been planning a framework for carbon trading for two years.

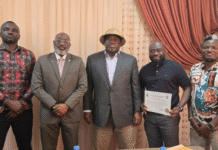

Dr. Emmanuel Urey Yarkpawolo, executive director of the Environment Protection Agency, told a COP29 side event that if it gets it right Liberia could make up to $80 million a year from carbon trading, equivalent to more than 10 per cent to the country’s annual budget. He said it could benefit local communities and support essential national development goals, including the expansion of renewable energy and road infrastructure.

But many communities and forest protection groups – alarmed by the Weah government’s apparent willingness to break Liberian law to make a deal with Dubai-based Blue Carbon last year – are demanding more transparency in those plans before trading begins.

By Evelyn Kpadeh Seagbeh with New Narratives